FOOT and mouth disease can be once again eradicated in Indonesia, if Australia's near neighbour is properly resourced.

Speaking following a visit to Indonesia, Professor Emeritus Peter Windsor from the University of Sydney said Australia had previously played a key role in eradicating the highly infectious livestock disease from both Indonesia and the Philippines.

"It's no easy task but firstly there has to be the necessary biosecurity, and that starts with movement control and hygiene," Prof Windsor said.

"Secondly, there needs to be the vaccines and the delivery of those vaccines to create a population that is less susceptible to the disease.

"Then there has to be the surveillance and the testing to show where the disease is and where it is not, and to detect any reservoirs of the disease, including in small ruminants.

"Finally there has to be sufficient public awareness so that everyone understands and cooperates with what is trying to be achieved."

Indonesia has about 65 million ruminant animals including about 16.5 million cattle. There is also nine milion FMD susceptible pigs.

As of August 3, Indonesian officials say some 934,000 cattle have been vaccinated.

The World Organisation for Animal Health estimates FMD circulates in 77 per cent of the global livestock population, mostly in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, as well as in a limited area of South America.

The current FMD outbreak in Indonesia has Australian authorities on red alert, as it represents an $80 billion threat to the Australian economy.

Prof Windsor said in addition to FMD, the World Organisation for Animal Health had also identified rabies, bovine tuberculosis, African swine fever, and peste des petits ruminants as diseases that could be eradicated.

The shining (and only) example of a livestock disease being eradicated on a global basis is rinderpest, which was officially declared to no longer exist in 2011, following the last confirmed case in 2001.

Prof Windsor said based on his experience and ongoing discussions with other animal health experts he said there was about 5 per cent chance of FMD reaching Australia.

While the virus was extremely infectious, it was also relatively fragile. A contaminated meat product that found its way into swill feed for pigs in a peri-urban area, or the malicious spreading of the virus were the two highest risks of causing an outbreak in Australia, he said.

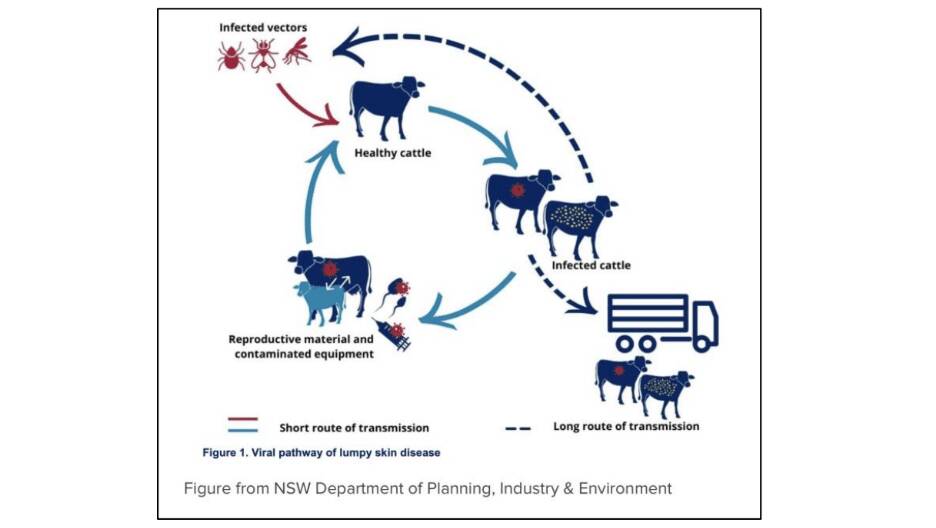

Lumpy skin disease was more problematic, he said.

While it was considered the "small pox of cattle" it was not regarded as a high priority disease and did not gain the same level of attention as FMD.

"Generally where lumpy skin disease appears, livestock producers find ways to manage it, particularly with vaccine use," he said.

Prof Windsor also rated the likelihood of LSD appearing in Australia as low, but said the risk increased if LSD was detected in Indonesia's eastern islands, and particularly if it entered Papua New Guinea.

However, he said it was unlikely to be transmitted by insects.

Transmission was more likely to be caused by movements of animals. People who crossed borders after they had been working with infected cattle could also be a problem, he said.

"Insects can really only carry the disease a short distance," Prof Windsor said. "It seems very unlikely LSD could be brought to Australia with monsoonal winds."