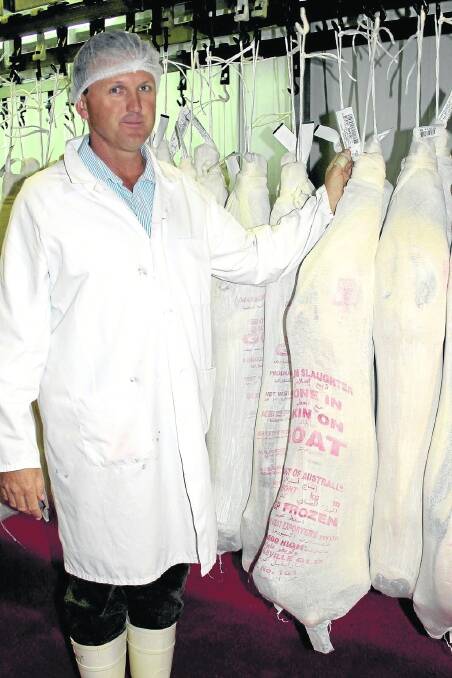

THE maturing profile of goats among producers in western parts of Queensland and NSW is evidenced by the booming business being done at Western Meat Exporters' plant at Charleville.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

The multimillion-dollar plant has been in operation since August 1997, when it was rebuilt after a devastating fire that destroyed the six-month-old establishment, and a number of new chillers were added as part of an extension plan at the beginning of this year.

Two 40-foot containers back up to the 1300-carcase capacity fridges for a daily trip to Brisbane's port, and this is set to grow.

The abattoir has a 100 per cent export focus, and director Campbell McPhee said that since free trade talks had begun with Korea, exports to the country had seen a 140-fold increase, just on the back of discussions.

"We are fielding a lot of interest from south-east Asia and India," he said. "I think a lot of our customers want to get in first."

New techniques to reduce hair contamination and modern equipment are also part of the plant's improvements to keep pace with the stringent health requirements demanded by overseas countries.

With livestock purchases of 16,000 goats a week, 185 people working in the abattoir and another 15 in the trucking company, goats have become an important part of the economy in the state's south-west, and Mr McPhee hopes producers are giving them serious consideration as part of their operations.

While prices fluctuate on a supply and demand basis, questions will continue to be asked about their place in a property's choice of animal to run, but Mr McPhee said there were now great opportunities for Queensland graziers to get on board.

He acknowledged that supply had diminished in recent years, partly due to weather and partly because of wild dog predation, and said 75pc of the abattoir's supply now came from NSW.

"There's a trend towards fencing country out in Queensland now, and I hope the people doing it are considering goats and including them when they think about how to help their country recover.

"Goats are very good for country."

With fencing comes evolving management of goats, and Mr McPhee was quick to caution potential suppliers that goats were no longer second-grade citizens.

"They need to be treated in the same way as sheep are, taking care to draft them into different grades and not having slip hazards when trucking, or it leads to bruising."

The company uses its own trucks to collect goats from properties and depots, but it urges graziers to communicate needs well beforehand so that kill space and trucks are available.

It is all part of a streamlined operation that sees 3000 goats a day processed at the Western Meats Exports Charleville base. As company attention moves more towards Asia and its desire for a whole carcase that can be cut to requirements, the line on the abattoir floor moves 6.5 goats every minute.

Sprays and vacuums are in constant use to achieve zero tolerance hair control; workers have colour-coded hairnets and coats to show what jobs and parts of the plant they are allowed to be in; and separate smoko rooms have been set up to prevent possible contamination between different parts of the plant at rest times.

"Back before the abattoir started, it cost the government $16 million a year to control goats, when they were called pests," Mr McPhee said.

"Now we've turned it into a large export market becoming a valuable part of the economy."